The Thomas Foundation’s Mission:

To halt the alarming decline in Australia’s biodiversity.

Australia has more than 1300 unique mammals, birds, reptiles, fish and amphibians – the world’s greatest species diversity. Since European settlement there have been 88 mammal extinctions, and those left are facing decimation or worse.

With 30 mammal species and 107 bird species vulnerable to extinction, some critically, The Thomas Foundation set out to halt this alarming decline.

Established in 1998, The Thomas Foundation closed its books as a Private Ancillary Fund in 2020 having disbursed its corpus as planned.

Background image: Shark Bay WA Dugong and Seagrass World Heritage Area by Murray Foubister via Wikimedia Commons

This is the story of a couple who made a fortune – then gave most of it away.

Barbara and David Thomas

Philosophy of a philanthropist

This is the story of David and Barbara Thomas, and an account of their philanthropy.

So successful was their strategy that for every $1 they gave to projects they supported, it’s estimated another $22 was given to these projects by others.

Reviewing The Thomas Foundation’s achievements, businessman and Federal Government policy adviser David Gonski says: ‘Australia needs more David Thomases’.

Their business – Cellarmaster Wines – was a spectacular success. David conceived the idea in 1980 when he was working in the Tasmanian Government’s European marketing office in London.

Reading The Sunday Times over breakfast, they ordered a case of Bulgarian wine through the newspaper’s wine club. When within a few days it arrived on the doorstep of their London home, the idea for a mail-order wine-business in Australia was born.

Just 15 years after its 1982 launch Cellarmasters had 200,000 customers accounting for 7 per cent of Australia’s bottled wine sales. Then in 1997 it was bought by Fosters and David and his wife Barbara made a decision that most Australians still find astonishing – to give away most of their fortune.

As David put it: “We had more money than we could ever spend, and it seemed natural to support others, to make good things happen that wouldn’t otherwise happen. We also wanted philanthropy to become as normal among Australians as it is among Americans.”

One of their earliest philanthropic ventures was to provide funding for Smith Foundation tertiary scholarship scheme, into which they injected about $500,000 with it becoming one of their proudest achievements. It was taken over and scaled up by Westpac Bank, an early example of the leverage that David was to seek in all future charitable investments. This radically transformed the Smiths from a traditional social welfare charity to one focussed on providing educational opportunities to financially disadvantaged children of all ages. It was then they realised they wanted to formalise their philanthropic activities, by establishing TTF.

The Smith’s Learning for Life program continues today, helping around 140,000 disadvantaged children a year. David maintains an interest in the program, recently contacting Smith’s chairman Nicholas Moore to re-propose a graduate-guided mentor program to assist new scholarship awardees.

It was then they realised they wanted to formalise their philanthropic activities, by establishing TTF.

“Philanthropy can be defined as strategic giving,” David says. “A charitable foundation is like a company, but managed in a way to deliver charitable services instead of financial profit.”

Modest backgrounds

Barbara was from a Hobart working class family. David’s early life was also marked by financial pressures and emotional challenges – with two sisters, he was raised in Hobart by their mother after the premature death of their scientist father when David was just 16.

David’s earliest awareness of wealth inequality came through frequenting Fullers Bookshop, heart of the cultural and jazz scene in Hobart, where he was introduced to authors such as John Steinbeck, John Dos Passos and Upton Sinclair.

David recalls:

“From our personal experiences we didn’t buy the argument put by some that because they pay their taxes it is the government’s responsibility to look after people in need. We knew that didn’t always work, and we wanted to do something about it ourselves.”

David and Barbara’s early broad vision was for The Thomas Foundation to develop the talent and creativity of Australian and New Zealand youth and artists, effecting cultural and social growth, and environmental conservation. Then they narrowed their focus.

Keith Cottier AM

Director 1998-2007

Max Bourke AM

Director 1998 -2008

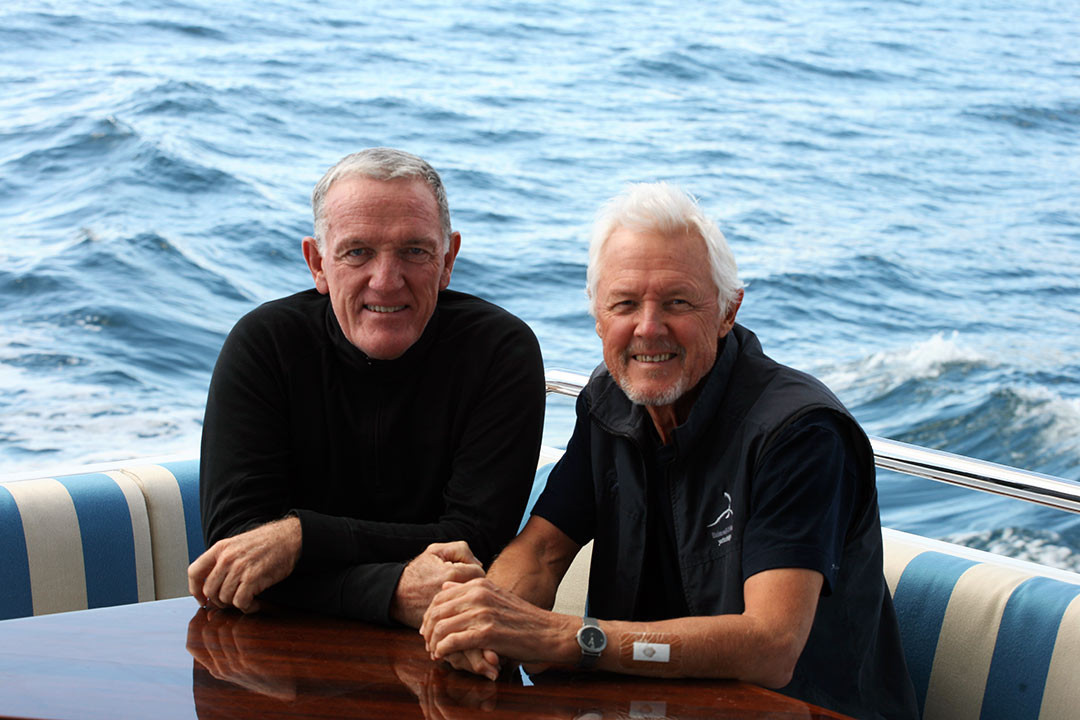

John Elmgreen (left) with David

Director 1998 – 2020

In 2006 with advice from Thomas Foundation Director Max Bourke AM, a scientist and retired former Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Heritage Commission, and supported by Directors John Elmgreen and Keith Cottier AM, they toured private conservation projects including fledgling ventures by Bush Heritage Australia, and the Australian Wildlife Conservancy. This led to the ‘Mildura Declaration’, drafted by TTF’s Directors sitting outside the light aircraft terminal at the Mildura Airport, that refocused the Foundation’s strategy on environmental conservation, with some support for the health sector and the arts.

The core strategy of the Mildura Declaration was the David Thomas Challenge – David and Barbara’s decision to commit $10m to private conservation projects, provided their commitment was matched by private donations. With the tighter focus, David and Barbara redefined the Foundation’s mission ‘to halt the alarming decline in Australia’s biodiversity’.

This was an objective beyond most people’s imagination, but not David’s.

In reality, the objective of halting biodiversity decline was a stretch target – (The Nature Conservancy’s former global chief scientist Hugh Possingham – a University of Queensland senior academic – estimates that over the past 20 years Australia’s biodiversity declined 20 per cent). Dr Aaron Bernstein, the first David Thomas Conservation Orator, and Professor David Lindenmayer of The Australian National University, reinforce David’s view that the decline must be recognised and tackled.

Dr Bernstein co-edited with American Nobel laureate Dr Eric Chivian, the scientific tome ‘Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity’. They set out in layman’s terms the real and direct links between human health and species’ preservation, and speculated on what research into natural processes would yield, including a new generation of anti-biotics. Further underlining David’s concern for biodiversity decline the Thomas Foundation sponsored an Australian National University workshop on Longterm Biodiversity Monitoring aimed at ensuring the efficient allocation of conservation resources, convened by Professor Lindenmayer.

“In everything I’ve done in business I’ve always aimed high – and to achieve even modest objectives I believe Foundations must do the same.”

Invited with Max Bourke to a strategy meeting of Bush Heritage Australia (BHA) in 2006, David successfully urged them to raise their fund raising ambitions from hundreds of thousands of dollars to more than $1m annually – a goal beyond their contemplation. BHA took up the challenge, and their success transformed the organisation.

In January 2020 when the Foundation was wound up, the final analysis showed environmental conservation received 83 per cent of the Foundation’s total distributions, health 7.3 per cent, education and welfare 4.5 per cent and the arts 2.4 per cent.

Fewer than one-in-ten US foundations make 75 per cent of their grants in a single field, and only 5 per cent focus more than 90 per cent in a single field.

“To have impact you must have focus,” David says. “The Foundation’s record reflects this. Others can judge our impact but I am satisfied with what we achieved. To halt biodiversity decline was always an aspirational target.”

The Foundation had great success on many fronts.

for example:

Leverage

These included:

Butler’s Dunnart Sminthopsis butleri (Simon Ward)

Dr Michael Looker and David at the launch of the David Thomas Challenge

the David Thomas Challenge

$8m distributed by TTF delivered $28m to private environmental conservation – and the Challenge was subsequently judged to be in Australia’s top 50 conservation gifts.

A TNC diver in Port Phillip Bay.

the Great Southern Seascapes

$4m from TTF, delivered $18m to rebuild shellfish reefs in coastal bays and estuaries, with projects underway in four States in 2020 – and a TNC objective of generating a $100m 60 reef program within six years of the program’s start.

Diving on the Great Barrier Reef.

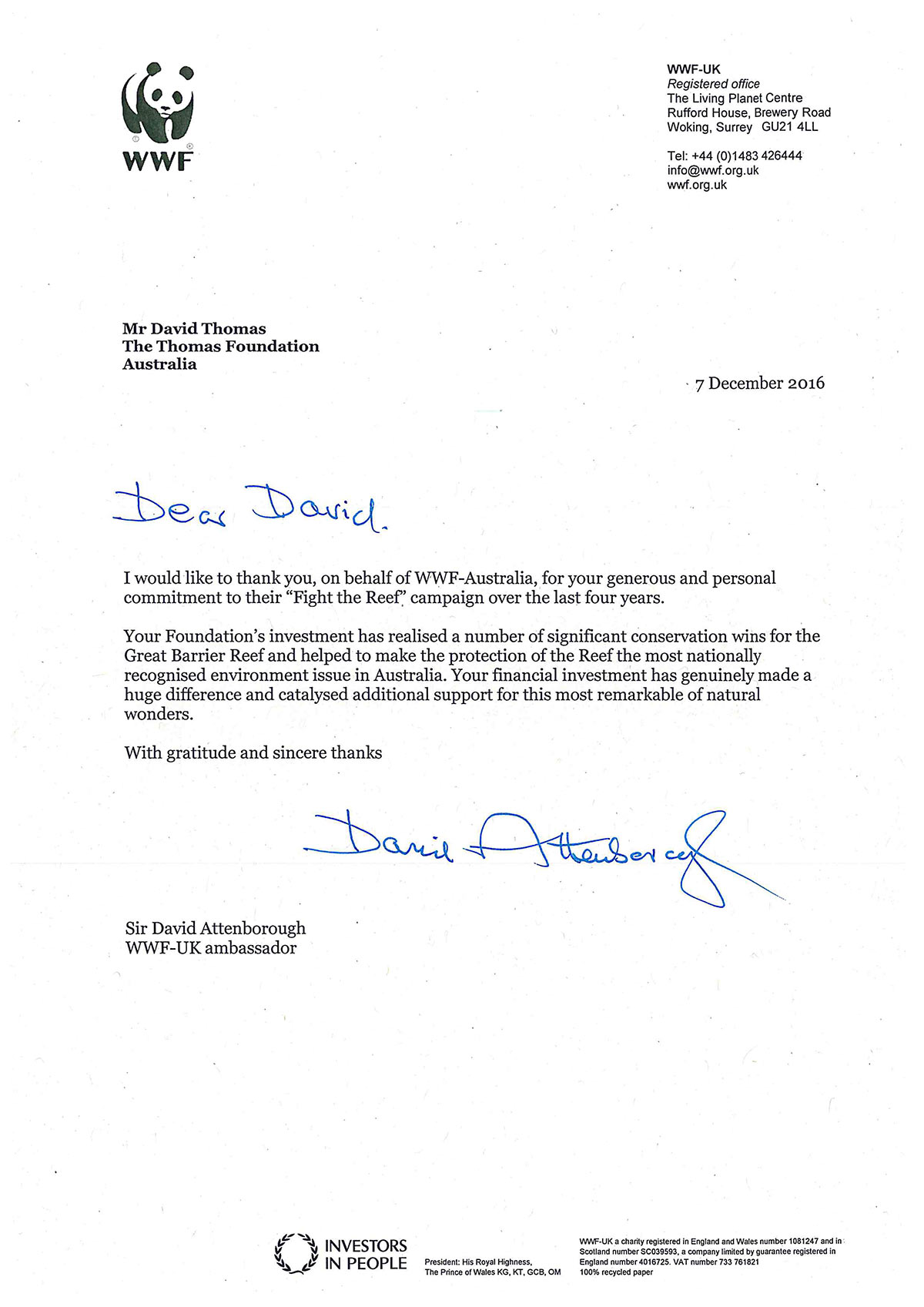

Fight for the Reef

$3.5m from TTF, delivered a $10m Fight for the Reef campaign by WWF and AMCS. In addition, responding to the public impacts of the campaign, the Queensland Government allocated $100m to reduce pollution and improve the quality of ground water run-off entering reef waters, and the Federal Govt controversially granted $440m to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation ‘to improve the health of the Great Barrier Reef and to leverage further funding’.

Northern Australia has a population of about 10,000 dugong living on sea-grass meadows found mainly in shallow waters from Shark Bay in the west to Moreton Bay in the east.

State waters marine parks

Establishment of State waters marine parks in Western Australia and the Northern Territory ($3m from TTF brought a matching contribution from the Pew Charitable Trusts, and $151m in research and management grants from the Western Australian Govt).

David Thomas at an AEGN strategy meeting.

AEGN

Australian Environmental Grantmakers’ Network (AEGN) – $1m from TTF delivered a matching $1m from other philanthropists to establish a sustaining fund.

Philanthropic Expansion

There are now more than 1600 Private Ancilliary Funds (PAFs) in Australia. A PAF enables a donor to gift into a trust tax-deductible funds that they plan to give to eligible charities over the longer term. They evolved from Private Prescribed Funds (PPFs) and before that Private Foundations. Today total value in PAFs is around $8bn. They distribute about $500m a year.

Motivation

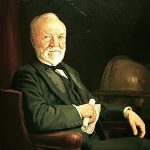

Andrew Carnegie

One of David and Barbara’s inspirations was US steel baron Andrew Carnegie who gave away more than $350 million and established the settings for the USA’s ‘third sector’ where private donations fund non-government projects delivering public benefit. Carnegie was also the first to unequivocally declare that the rich have an obligation to give away their fortunes. In 1889 writing The Gospel of Wealth he asserted that all personal wealth beyond that needed to meet the needs of one’s family should be regarded as a trust fund to benefit the community.

Andrew Carnegie has a little known philanthropic connection with Australia – the building of public libraries in Hobart, Northcote and Mildura (Vic), and Midlands (WA), four of some 2500 libraries he supported worldwide.

Frank Hanna

American merchant banker and philanthropist Frank Hanna was similarly motivated, dividing his wealth into what he termed the ‘fundamentals’ and the ‘non essentials’. Hanna’s view was that the ‘fundamentals’ are for all the things needed for individual development and to support dependents; and ‘non essentials’ are the remaining surplus – all of which Hanna says should be given away. He detailed this philosophy in his book What Your Money Means and How to Use It Wisely, published in 2008.

David and Barbara decided on a similar approach nearly two decades earlier. As Australia prospered – baby boomers’ inheriting family wealth, executive wages moving to international parity, and individuals’ wealth accumulating beyond the wildest dreams of earlier generations – the Thomases set out to encourage the distribution and fairer sharing of this largesse.

Validation

Joel Fleishman

… more than just writing cheques”

The inspiration was one thing, but there was also the challenge of effectively dispersing their wealth. For advice the Thomases first turned to Joel Fleishman, professor of law and public policy at Duke University. In The Foundation: America’s Great Secret, Fleishman wrote that Foundations serve a vital social function providing seed funding for innovative initiatives. Directors of the Thomas Foundation were expected to have biblical knowledge of Fleishman’s philosophy. Would-be philanthropists were given copies of his book.

Mark Kramer

Michael Porter

David also read papers by Michael Porter – Harvard University Economics Professor, business strategist, social policy theoretician and author. One in particular – Philanthropy’s New Agenda: Creating Value – by Porter and his colleague Mark Kramer – deeply influenced David. Together Fleishman, Porter and Kramer re-inforced the Thomas’s conviction that strategically delivered and implemented ideas are powerful tools that can change society for the better.

Realising foundations’ potentials

As well as encouraging wealth dispersal, Porter and Kramer also advised foundations to support only the best performing organisations, and then to help them further build their capacity.

Conservation focus

For David, a life-long bush-walker and fly fisherman in Tasmania’s pristine environment, the shift in focus brought about by the Mildura Declaration was a comfortable fit for his ambitions.

“You can’t be a fly fisher or a bush walker without being deeply aware of the environment and concerned for its future,” he says.

The challenge then became identifying organisations with the experience and resources needed to achieve the high aims and ideals David and Barbara sought.

Globally 177,000 sq kms of vegetation are being cleared each year with eastern Australia one of the world’s 11 de-afforestation ‘fronts’ where forests are most at risk.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC)

With Rob McLean, then Chief Executive Officer of McKinseys Australia, David set about persuading TNC – the international behemoth among conservation organisations with 1 million members, assets of $1bn, 4000 employees including 600 scientists, and with projects in 74 countries, to establish a presence in Australia. He’d met some of its largest donors fly-fishing in Russia and South America and was impressed that people who seemed the opposite of ‘greenies’ felt passionately about conservation. It’s a hugely ambitious and inventive science-driven organisation, and David sponsored one of its senior officers Dr Peg Olsen to scope its establishment here. As a result, with Rob McLean, she convinced TNC’s executive to open an office in Melbourne. It was initially headed by Kent Womack, from TNC’s Executive Office in Washington. Since its establishment in the late 1990s, TNC Australia has consistently delivered programs from landscape-scale terrrestrial conservation, to indigenous engagement, shellfish reef restoration, a world-first impact water investment project in the Murray-Darling basin, and a metropolitan forrestation project in Melbourne with plans to roll it out in all metropolitan cities. Botanist Dr Michael Looker, previously head of the Trust for Nature in Victoria, was the first Australian appointed as TNC’s country director. Rich Gilmore was Country Director for the six years to 2020.

Since 1998 The Thomas Foundation and David personally have contributed about $20m to TNC’s projects and programs and significantly influenced its direction and development. David sees his part in wooing TNC and supporting its establishment in Australia as his most important conservation legacy.

“It’s a quality organisation, deeply experienced with high-quality staff,” David says. “It is delivering innovative world-leading programs here, and will continue to do so for years to come.” In mid 2020, TNC took the transformative step of establishing a $5bn natural capital investment fund – the project to be led by Rich Gilmore. Rich is drawing on his experience in establishing the Murray-Darling Basin Balanced Fund, a world-first and new model for how agriculture, conservation and the economy can thrive together.

Taking further advice from Porter and Kramer to avoid passivity, David earned the reputation among conservation NGO’s as an ‘interventionist investor’.

“All small business people are money conscious,” David says. “I was no exception and wanted to make sure our money was being well spent and not squandered.

“I was never going to just sign the cheques without any involvement, or the involvement of one or more of my directors. We set KPI’s, and funding commitments were only fulfilled when the KPI’s were met, often after independent audit or peer review.”

Hawksbill turtle – critically endangered; sponges are the Hawksbills’ main food. Threats are anthropogenic.

Increasing public awareness of the threats to Koalas from habitat loss, chylamydia, dogs and vehicle strikes.

“Barb and I were also conscious that as we were getting a tax concession we had to deliver real benefits to the Australian community at minimum cost,” David says.

Over the life of the Foundation, costs were held to a very lean 5.1 per cent of grants made.

Further, net investment income earned on the Foundation’s Corpus over its life not only met these costs but enabled a further $3.1m to be distributed in grants.

As David puts it, they wanted ‘to give with a warm hand’. So their plan was to distribute about 15% of the Foundation’s funds annually, meaning it would be wound up on David and Barbara’s 80th birthdays in 2018.

“This also meant the tax deduction delivered a public benefit now, rather than being locked away as often happens with Foundations in the USA.”

Leverage benefits

David Thomas Challenge

David Thomas, fly fisherman

The first innovative conservation venture was the David Thomas Challenge to which the Foundation committed $10m and eventually outlaid $8m. Results of the David Thomas Challenge included:

- acquisition of six new conservation properties totalling nearly 1m hectares of some of Australia’s most threatened habitats and species

- management of six other properties totalling more than 1m hectares

- conservation management of more than 3.3m hectares of land though four projects managed by indigenous communities, and support for the declaration of two Indiginous Protected Areas totalling more than 2m hectares; and

- landscape scale management of six properties – all biodiversity hot spots, a criteria that was applied to the whole project

The David Thomas Challenge attracted $12m in support from Australian philanthropists and more than $1.2m from US philanthropists. The Federal Government allocated $6.2m to expand the Federal Reserve System.

The land purchases were made through Bush Heritage Australia, Australian Wildlife Conservancy, Greening Australia, Trust for Nature and Birds Australia.

After this success, Professor Gene Likens, the scientist who identified ‘acid rain’, reviewed the Foundation’s program. He noted that the Foundation had neither marine nor fresh water projects in its program. As a result three ambitious marine projects emerged – Great Southern Seascapes, possibly the Foundation’s most important legacy project; the Fight for the Reef campaign; and the northern waters campaign that led to the declaration of the Great Kimberley National Park.

Great Southern Seascapes

Restoring oyster reefs

To fill the marine shortcoming identified by Professor Likens, Lyn Zeitlin Hale, then head of TNC’s Ocean Program pointed to its success with Oyster reef restoration projects in the USA, and suggested Australia was ripe for a similar initiative. From an experts’ workshop a plan was devised to restore reefs once ubiquitous to Australia’s bays and estuaries, and vital to biodiversity and species health, but nearing extinction.

With a $4m Thomas Foundation commitment over three years, the Great Southern Seascapes program was begun in Port Phillip Bay. Now there are shellfish reef restoration projects in Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia and Queensland and TNC has a target of restoring or protecting 60 shellfish reefs in the next six years in a $100m program. The TNC objective is for Australia to be the first nation in the world to recover a critically endangered marine ecosystem.

In Queensland a reef and estuary restoration project is underway in Noosa – the coastal resort town David has called home for the last 22 years – with research funding from The Thomas Foundation and seed funding for its implementation from David, delivered through TNC.

Now retired from TNC, Lynne Hale recently reflected: ‘GSS remains one of the most notable conservation successes I know of. I continue to use it as an example of the secret cause for conservation success. This is how GSS was born. The sauce requires two ingredients: A generous and visionary donor (in this case David Thomas) willing to take a calculated risk provided the risk is backed by a strong requirement for accountability (in this case annual reviews of key performance indicators by a panel of independent scientific assessors).’

Fight for the Reef

Christmas tree worm on the Great Barrier Reef

“In 2013 we moved into political advocacy in an area that seemed desperately in need of new solutions,” David recalled. “Existing environmental policies were clearly unable to protect the Great Barrier Reef from agricultural expansion, and from industrialisation of the Queensland coast.”

The Reef’s World Heritage listing in 1974 came at the end of a decade of political wrangling first over mining the reef for limestone, then drilling for oil. It took a Federal and State initiated Royal Commission to resolve the push by the Bjelke-Petersen Govt for unlimited oil exploration across the Reef. At the end of this, most Australians assumed creation of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) in 1976 protected it for all time.

But the marine park was on the edge of a frontier state long dependent on natural resources. Many people have since come to understand that this is a place where real protections are grudgingly conceded because of the tension generated by expectations for continued economic growth.

Judith Wright, one of the leaders of the first reef protection campaign in 1967, recognised this tension when she wrote: “The forces that want to exploit the Reef’s oil and mineral resources are (so) immense, it seems laughably unlikely that successive Federal and State Governments will not undo (these protections).”

By 2010 the ‘undoing’ she forecast had begun – but few noticed. Led by gas miners, Gladstone’s expansion into a mega LNG exporter had begun, regardless that it was adjacent to the World Heritage Area. Expansion of Queensland coal export ports also adjacent to the Reef was planned, including creation of the world’s biggest thermal coal port at Abbot Point. Environmental and political groups were aware of the plans – among them Greenpeace, Sunrise and Getup.

As The Thomas Foundation considered its first round of funding for the campaigning partnership it had encouraged between the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF Australia) and the Australian Marine Conservation Society (AMCS), public attitudes were polled. It found wide public pride in the Reef, and a sense of national ownership. The vast majority saw the Reef’s World Heritage listing as strengthening Australia’s international status; and more than eight out of 10 rated the Reef’s protection as Australia’s most important environmental issue. Most assumed the Reef’s World Heritage listing protected it. Few knew of the extensive industrial development underway or planned and the increase in shipping traffic forecast through the Reef – and when told they were alarmed.

David was pro-environmental protection but not anti-development. Separating the two was challenging for the Reef protection campaigners.

He recently reflected: “Our environmental protection campaign was inevitably caught up in the climate change and anti-coal mining campaign.”

It wasn’t long before the Queensland Resources Council declared: “These extreme groups should recognise reality instead of scare-mongering with their misleading claims about climate change and the environment.”

“I had assumed there would be some emotional memory from the Judith Wright-led campaign to protect the Reef in the 1960’s and ‘70’s, but this was not as deep as I had hoped,” David recalled.

At the launch of the Fight for the Reef campaign Bob Irwin, Australia Zoo founder and conservationist, memorably said: “It’s your Reef and you’re going to have to fight for it”.

Open letters from Reef scientists and marine biologists were sent to the Prime Minister. An independent expert review of Government reef protection policies found many inadequacies.

“It shocked us when the Australian Government used its international influence to counter these expressions of concern and lobbied the 22 Governments of the World Heritage Committee to head off the Reef being declared in danger – at a time when its own State of the Reef report showed it was already in desperate trouble. At that time no other government had lobbied WHC in this way. It was short sighted,” David said.

Since 2016 – just a year after this lobbying – there have been three coral bleaching events resulting in the loss of 50 per cent of shallow water corals, according to Reef experts.

“A more effective Federal Government response would have been to harness the public outrage generated by an ‘in danger’ listing and fix the problems. It could have been a nationally inspiring initiative.

“But the miners said it was against their interests, and the government listened to them, and not to the campaigners.”

Subsequently through the Freedom of Information Act The Thomas Foundation tried to understand the Government’s action and reasons for this international lobbying. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade blocked access – releasing some 30 memos and minutes but with their content entirely redacted (blank pages with a black ‘X’ across each).

The GBR Taskforce’s spending was declared to be $218,132.27 for the period August 19, 2014 to April 2, 2019.

It took the Government 19 weeks to provide this and 57 essentially blank pages.

Despite unprecedented government lobbying in this international forum, and the attacks by the mining companies, the Fight for the Reef campaign achieved significant change in Federal and State Government policies to protect the Reef, including new regulations and legislation that;

- halted new port development;

- stopped dumping of dredge spoil in World Heritage Waters;

- reformed governance for the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: and

- reformed navigation and fishing.

There were prominent supporters too – including US President Barak Obama, Prince Charles, David Attenborough, Leonardo DiCaprio, Callum Roberts, Simon Baker, David Williamson and Tim Winton.

The campaign turned public complacency into political potency with the Fight for the Reef becoming an influential issue in Brisbane metropolitan seats in the 2017 Queensland State election. The resulting Queensland Labor Government subsequently appointed Australia’s first Minister for the Great Barrier Reef.

Great Kimberley Marine Park

Great Kimberley Marine Park dolphins are subject to intense research programs.

“2013 was also the year we joined the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Australian Marine Conservation Society (AMCS) and other groups in another ambitious advocacy program – to protect State-controlled waters along the coast of northern Australia, in the Kimberley and the Northern Territory”, David said.

Both are home to some of the least disturbed tropical waters on earth, but then with little legal protection. The bays of the central Kimberley coast are home to the largest humpback whale nursery in the world, some of the foreshores are the summer feeding grounds for several hundred thousand migratory birds, and the waters are among the last remaining large refugees for many threatened and endangered species.

The Foundation committed $3m over three years and scientific, public and political support was steadily built with the WA Govt declaring the first section of the Great Kimberley Marine Park. It now comprises 344,000 sq km of protected waters.

TTF’s $3m enabled the conservation groups to leverage a further $151m from the Western Australia Government to fund research and management.

Barry Traill

“This is a testament to the vision of David Thomas – his willingness to stay the course, his understanding of the political process, his commitment to collaboration, and his passion for this country,” Barry Traill, then Pew’s Australia program manager said.

Darren Kindleysides, CEO of the Australian Marine Conservation Society, said: “David’s support for protecting Australia’s oceans has been transformational. Thanks to David’s major commitment, the Australian Marine Conservation Society and The Pew Charitable Trusts were able to create a coalition that established the Great Kimberley Marine Park and the process and pathway for a marine park network in the Northern Territory.”

Fellowships and Conservation Orators

Barbara Thomas

The Foundation’s gifting was not only to projects and land purchases. It has also supported numerous fellowships, science and technology awards and student conferences.

In 2009 the Foundation established the David Thomas Conservation Oration which brought renowned conservationists to Australia to raise professional knowledge and public awareness about issues critical to safeguarding biodiversity.

The stellar line-up of David Thomas Conservation Orators included

- Professor Daniel Pauly, of the University of British Columbia, who developed the concept of ‘shifting baselines’ in popular appreciation of fish stocks, author of several books and more than 500 scientific papers;

- Professor Callum Roberts, of the University of York, author of three books and major contributor to a global data base of coral reef marine diversity;

- Wade Davis, anthropologist and Explorer in Residence at the National Geographic Society, author of 11 books;

- Dr Aaron Bernstein, Director Harvard University’s Centre for Climate, Health and the Global Environment, co-editor of Sustaining Life: How Human Health depends on Biodiversity;

- Harvey Locke, recognised global leader in large landscape scale conservation and convenor of the Yellowstone to Yukon initiative; and

- the Hon Robert Hill, AC, former Australian Minister for the Environment, Global Ocean Commissioner and Adjunct Professor in Sustainability at the US Studies Centre, University of Sydney.

Barbara Thomas Fellowships

Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing (CHeBA)

David Thomas AM

HammondCare

Director of Music Engagement, Dr Kirsty Beilharz & a resident at HammondCare North Turramurra

In 2013 The Thomas Foundation committed $1.25m to HammondCare, a charity providing aged, dementia and palliative care, and rehabilitation and pain management needs. The Foundation’s grant is to support HammondCare’s participation in the National Health and Medical Research Council’s project, ‘Dealing with cognitive and related functional decline in the elderly’

In 2014 The Thomas Foundation funded The HammondCare Music Engagement Project with a $250,000 grant. The project aims to use music to improve quality of life for people in need.

Self effacing

David says of himself that some might see him as egotistical; but he has alway felt insecure even though driven to win.

David and Barbara sought nothing in return for their philanthropy – avoiding the public and media spotlight whenever they could. David declined even to attend the David Thomas Conservation Orations.

In his study there is no ‘power wall’ of photographs typically found in successful people’s offices. Rather, reflecting another of David’s great interests, behind his desk is an intriguing work by internationally recognised American glass artist William Morris. It closely resembles a piece by Morris, prominently displayed in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art – but in San Francisco the work is in a glass case to ensure its security. In Noosa it’s splendid in its open display. Reflecting their interest in this art, David and Barbara were generous donors to Ausglass and to the Canberra Glassworks.

David’s glass art collection regarded as among the best private glass collections in Australia is destined for the National Gallery of Australia.

David has also been a significant supporter of the Australian Chamber Orchestra.

Admired for his generosity and paradigm-changing approach to wealth distribution through philanthropy, David is widely read and broadly knowledgeable, causing some to perceive him as being arrogantly opinionated. I hadn’t known Barbara long when at a dinner where David was being particularly assertive, she said to me: ‘My mother often said David was like a lobster – all arms and legs with shit for brains. Don’t you ever forget that!’

David maintained their philanthropic pursuits after Barbara’s death in 2015, and has made provision to continue chasing their goals posthumously, assigning the bulk of their estate to conservation organisations.

“I hope we have helped spawn new generosity in Australia with more Foundations efficiently re-distributing people’s wealth under these results-oriented business principles,” David said.

He was awarded a Medal in the Order of Australia (OAM) in 2007 and became a Member of the Order (AM) in 2014. He sought neither accolade but was nominated and supported by others with knowledge of his philanthropic pursuits.

Fittingly the Foundation’s last funding decision in December 2019 was to give a further $500,000 to the Barbara Thomas Scholarship fund to be administered in perpetuity by TNC. An initial $500,000 was given to establish an annual Barbara Thomas Fellowship program in 2005.

David has never lost his relentless drive and interventionist inclinations. In the aftermath of the 2019-20 national bushfires, David re-activated contacts in the environmental sector, expressing the fury many in the community felt for the Federal Government’s denial of anthropogenic climate change and its frivolous factional politicking around the issue and criticising the NGOs he had supported for their lack of a public voice of condemnation – never mind that the Foundation had been wound up. This is the interventionist philanthropic investor at work, exercising influence and the public obligation he still feels.

Rowland Hill, Thomas Foundation Director 2007 – 2020

What some others say

First was his enormous generosity and modesty. He outlined his plan to fund his new Foundation and this was a bold and large commitment.

Second, he just didn’t want to make donations. He wanted to be a catalyst for positive change and increased giving. He particularly mentioned bringing business principles to giving, a very new idea in those days of philanthropy in Australia.

The success of his Foundation and the large and commendable effect it has had is no surprise to me, and I heartily congratulate him on what he has achieved.

We need more David Thomases!

With gratitude and sincere thanks.

David Thomas has always insisted on quantifiable outcomes and encouraged other philanthropists to join him in his quest to make a difference. As a direct result of the generosity of The Thomas Foundation, Australia has benefitted from an environmental legacy including the Great Barrier Reef, rivers, fragile ecosystems, and endangered species.Many environmental organisations have also been able to continue their programs and research as a result of support from The Thomas Foundation.

‘Few people are prepared to gift the vast majority of their wealth to a particular cause but thanks to the generosity of David and Barbara Thomas, Australian wildlife has been a major beneficiary.

I haven’t met a philanthropist giving to the environment who has advanced philanthropy more than David Thomas. What is distinctive about David’s contribution, supported ably by Trustees Max Bourke, John Elmgreen, Keith Cottier and Rowland Hill, is his business-like approach to environmental philanthropy. Business men and women who build companies, as David did successfully with Cellarmasters, do several things well. They leverage the equity in the business in order to grow, they seek scale to have a viable business, and they effect change by building an ecosystem around them with requisite skills. Let me illustrate how David brought leverage, scale and change management to environmental philanthropy in Australia.

The Thomas Challenge offered matches to other philanthropists for approved projects. It helped acquire iconic properties for conservation like Craven’s Peak for BHA and Kalamurina for AWC. The Challenge was so successful in gaining matches that the second round offered a half match! When TNC evaluated the Thomas Challenge they concluded that the $10 million on offer had catalysed $28 million of value. Now that’s leverage. David naturally wanted to see projects scale. When he decided to offer matched funding to TNC to restore Australia’s lost oyster reefs he saw the potential, validated by scientists, to bring back a marine ecosystem brought to extinction. Some 60 sites have been identified for projects, and reef building is now happening in 6 locations in Victoria, South Australia, Queensland and Western Australia.The Thomas Foundation funded Barbara Thomas Fellowships for exchanges of scientists in the environment, advocacy to change policy relating to marine protected areas and provided strategic funding for environmental grant makers through AEGN. David may not express it this way but through these initiatives the Foundation has strengthened the ecosystem for effecting change in the environment.

Rowland Hill, Foundation Director 2007-2020, with David Thomas. Rowland wrote this recollection of The Thomas’s motivations and The Thomas Foundation’s strategies and activities.